Zombies & Hoodoo & Zora Neale Hurston

"Belief in magic is older than writing."

You may know Zora Neale Hurston as a prominent voice of the Harlem Renaissance, author of Their Eyes Were Watching God. Did you know she was the first to chronicle African-American folklore and the spiritual practice of Hoodoo?

Zora Neale Hurston was born in 1891 (allegedly according to biographers, according to Hurston sometimes 1901, 1902, 1910, who needs details like age…) in Alabama, later moving to Florida when she was three. If you’ve read her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, a coming-of-age story about a Black woman in an all-Black Floridian town, you are well acquainted with her hometown of Eatonville, the first incorporated all-Black city, which serves as inspiration for the setting of many of her novels. Her grandparents were born into slavery. Her father was both the mayor and preacher of the town, and her mother a school teacher. When Hurston was only thirteen years old, her mother died and her father remarried. Due to friction with her stepmother, she was sent away to boarding school until her father was no longer able to pay for tuition. It is believed that Hurston began to lie about her birth year so that she could gain access to a free high school education. She began her college education at Howard University, earning an Associate Degree, and at the age of 25, won a scholarship to Barnard and transferred. An anthropology major, she graduated from Barnard College in 1928, as the college’s first Black graduate, and the first in her family.

During her time at Barnard, noted anthropologist and professor Franz Boas, “The Father of American Anthropology” (the scientific study, not the store…), was impressed by a term paper she submitted, and invited her to participate in conducting ethnographic research. In 1927, Hurston received a research fellowship from the Carter G. Woodson Foundation of $1,400 to work with Boas to study African-American folklore in the South. Her first trip to Florida was unproductive, as she failed to fully immerse herself in the community she was studying; a mistake she would not make again. She writes in her autobiography, Dust Tracks, published in 1942:

“When I went about asking, in carefully-accented Barnardese, "Pardon me, do you know any folktales or folk-songs?" the men and women who had whole treasuries of material seeping through their pores looked at me and shook their heads. No, they had never heard of anything like that around here. Maybe it was over in the next county. Why didn't I try over there?”

The following year, she spent in New Orleans, where she was initiated into the practice of being a Hoodoo doctor. Hoodoo is a blend of folklore, spirituality, and conjuring, native to Afro-Caribbean communities and the Deep South. For Westerners, their first exposure to Hoodoo was the 1929 bestselling book The Magic Island by journalist W. B. Seabrook, which of course sensationalized the practice. (Sidenote: this dude, who once was a Greenwich Village bohemian, went to Western Africa and engaged with a tribe who participated in ritualistic cannibalism and told everyone in his book Jungle Ways that he joined them in the practice. But it turned out he was a big fat LIAR and the tribe refused to let him eat and served him gorilla instead, so he went to the Sorbonne and “persuaded” a medical intern to give him a piece of a man who died accidentally… the answer you’re looking for is VEAL. I read that so you didn’t have to. You’re welcome). In 1931, Hurston published Hoodoo in America, a collection of accounts from fieldwork she conducted in New Orleans in 1927. Her initiation ritual included fasting for three days while laying naked on a couch with her bellybutton on a snakeskin beneath her, undergoing hallucinations and psychic visions. Her experience was so transformative that she was never able to write about the experience in detail. Hurston’s later book Mules and Men, published in 1935, is a collection of folklore from African American communities in the South, further detailing her experiences with several conjure doctors in New Orleans during the 1920s and 1930s.

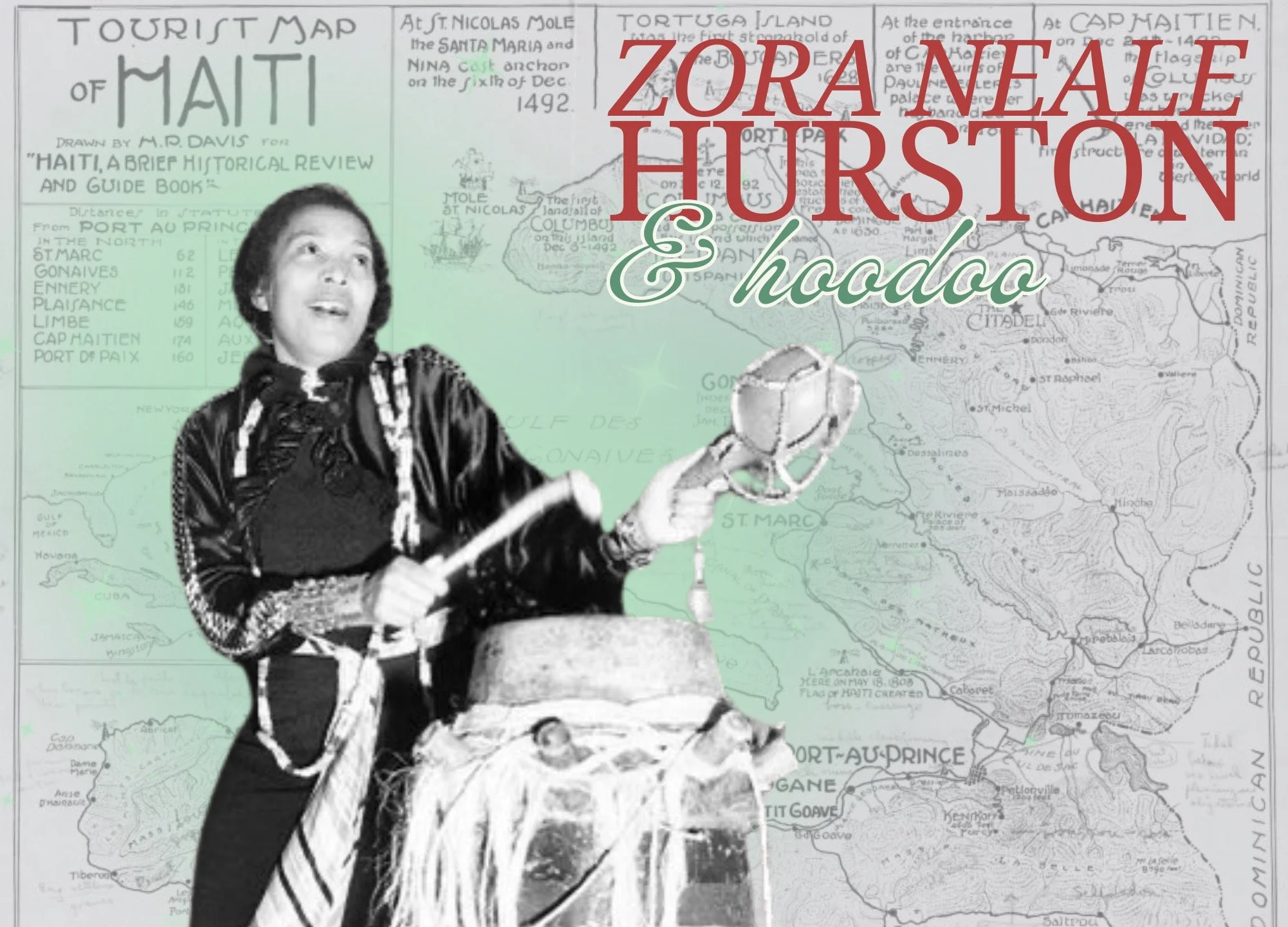

In 1935, at the height of the Harlem Renaissance, Hurston was to be enrolled in a doctoral program in anthropology at Columbia University through a fellowship sponsored by the Rosenwald Foundation. However, she was forced to abandon the program when funding fell through due to the Great Depression. She then applied to a six-month fellowship from the Guggenheim Foundation, which she was awarded, to travel to Haiti to study West Indian folk-life. In September of 1936, Hurston arrived in Port-au-Prince.

In 1938, Hurston wrote Tell My Horse, a non-fiction account of her experiences in Haiti and Jamaica, legitimizing Haitian Hoodoo as a spiritual and cultural practice. It is in this book that she introduced the American public to the concept of zombies. (Yes, before this, there were no zombies in American pop culture. Okay, fine, Seabrook also talked about zombies, but in a sensationalized ZOMBIES way, not in an anthropological way. Next year, when you watch the upcoming season of The Last of Us, make sure to pour one out for Zora). In Haiti, bokors (hoodoo sorcerers) can create zonbi (zombies) by poisoning victims with, what was once assumed and now maybe debunked, tetrodotoxin (like from the pufferfish) or bufotoxin (like from the toad). This poison is near-lethal, induces a coma, and can make the body of a person appear to be dead for several days. After poisoning, the person is buried and later exhumed by the bokor who revives them, or resurrects them, to do their bidding. The bokor continues to the drug the victim with a substance similar to Datura stramonium (allegedly), which places the victim in a conscious but susceptible and dreamlike state. A very elaborate and spooky tactic for human trafficking and forced labor. Check out the photo Hurston took of zonbi victim Felicia Felix-Mentor here, published in LIFE Magazine in 1937.

Have we piqued your interest yet? Good. Now go out and buy her books and read them.

Throughout her career, Zora Neale Hurston published four books, dozens of essays, short stories, and plays, and was a professor at many schools including North Carolina Central University (formally North Carolina College for Negroes). From 1957-1959, Hurston wrote a weekly column in the Fort Pierce Chronicle, a Florida newspaper, titled “Hoodoo and Black Magic”. Today she has inspired countless authors, including Black fiction authors who infuse Hoodoo traditions in slave narratives, such as Eden Royce, Tananarive Due, and of course, Toni Morrison. Yet at the age of 69, in 1960, she left this world, and was buried in an unmarked grave in Ft. Pierce, Florida.

In 1973, Hurston received a second life from beyond the grave. Pulitzer-winning author Alice Walker, most known for her novel The Color Purple, read and was inspired by Mules and Men, and decided to seek out Hurston’s grave and give her a worthy headstone. You can read her essay titled, “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston” (seriously, please read this), which was published in Ms. Magazine in 1975. Hailed as the “Patron Saint of Black Women Writers”: it is this praise that propelled Hurston’s legacy. When Their Eyes Were Watching God was first published in 1937, it was considered a commercial failure. Alice Walker’s essay led to its republishing, and it is now considered Hurston’s most esteemed work.

Zora Neale Hurston contributed not only to American literature, but more importantly to the preservation of African-American folk traditions. Her anthropological research and fieldwork, and investment in legitimizing the spirituality of Black people, especially Black women, was integral to her work as a fiction author, and without it, her legacy might have been lost to the ages.